Originally published by the United Nations Industrial Development Organization on 17 September 2020

|

|

There are currently only 63 economies in the world classed as industrialized, making up less than 20 per cent of the global population. Yet, together they produce over half of the world’s manufactured goods. Emerging economy China alone churns out a further 30 per cent.

In startling contrast, the 47 least developed countries (LDCs), which make up 13.4 per cent of the world’s population, produce less than one per cent of manufactured goods. Other developing countries do only a little better, together producing just two per cent.

There is now a risk that, as a result of the ongoing economic shockwaves from the COVID-19 pandemic, the gap could widen even further. Manufacturing growth in LDCs is grinding almost to a halt. Forecasting that 2020 will be the worst year for global manufacturing output since official records began, UNIDO expects manufacturing value added (MVA) as a share of GDP – a key indicator equivalent to net output of goods – to grow in LDCs by a negligible 1.2 per cent in 2020 compared to 8.1 per cent in 2019.

This matters because for developing countries, and LDCs in particular, strong growth in manufacturing industry is a key driver of sustainable development. More than that: it has a significant impact on economic and social well-being in those countries, as a recent report by UNIDO demonstrates.

This might not seem surprising. We know almost intuitively that those living in rich, industrialized countries enjoy higher standards of living and better quality of life as a result of higher levels of education, more advanced health care, a wider social safety net, better transport and access to technology.

But pinning down how such indicators should be measured is itself an inexact science. Economists have begun looking beyond GDP as a barometer of economic health, and are increasingly including measures of well-being. These include the frameworks provided by United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Human Development Index (HDI), the Happy Planet Index, the World Happiness Report, and the OECD’s Better Life Index. But there is still no consensus on what should be included in the calculation of well-being, and many of the indicators remain subjective rather than empirical.

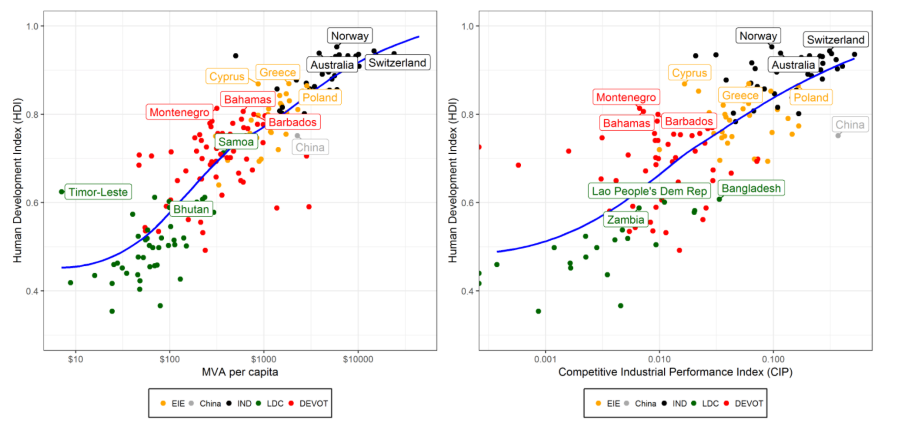

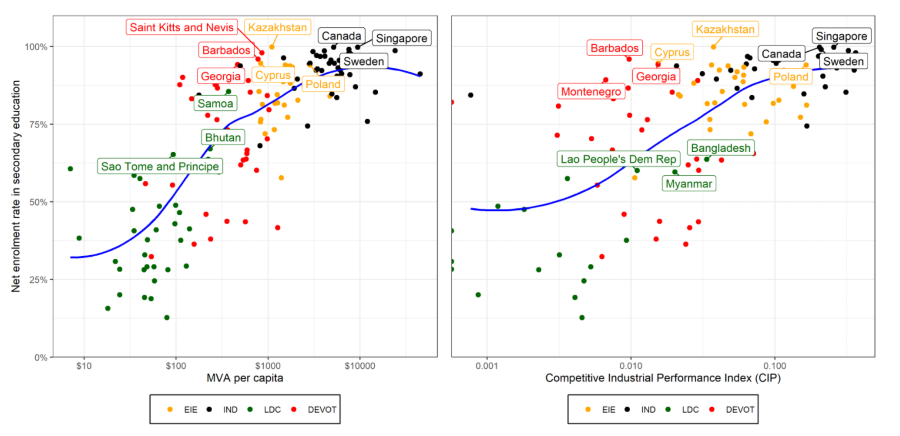

The UNIDO report looks at data across all countries. It plots MVA per capita – along with competitiveness measured by UNIDO’s Competitive Industrial Performance (CIP) Index – against indicators on poverty, inequality, health, education, employment and human development. The results provide clear statistical evidence on how closely the process of industrialization is connected to people’s living conditions and their quality of life, showing precisely how Sustainable Development Goal 9 on industrial development links to a broad range of other development goals.

On a whole raft of indicators, it is plain that the benefits of a thriving industrial sector spread well beyond mere growth rates for developing countries. Without greater industrial development those benefits will remain elusive for millions of people.

The report highlights, for example, the key role that industrialization plays in human development. Its impact on technological change and innovation boosts skills and learning, enables the creation of essential goods, and drives social change. Measured against UNDP’s HDI and Inequality adjusted HDI (2018), it finds clear similarities between high MVA per capita and high HDI values, with European and North American industrialized countries at the top and LDCs in Africa and Asia at the bottom.

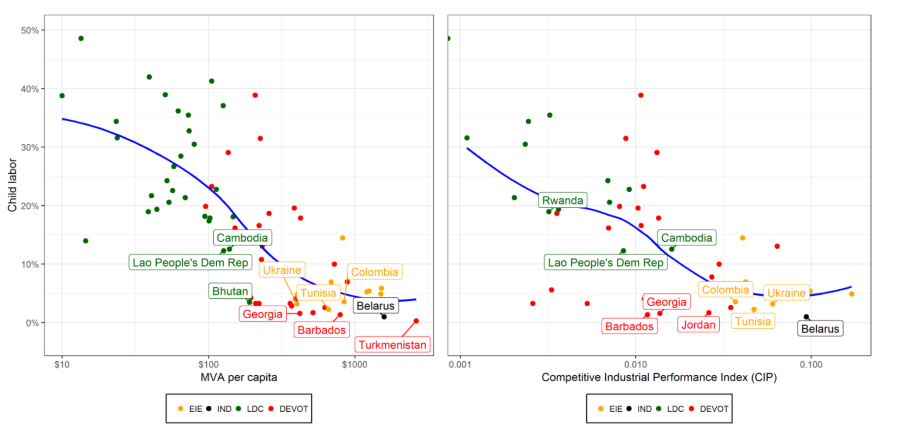

It shows the impact of employment on well-being too. As labour productivity goes up, employers are more able to provide higher-skilled and higher-paid jobs, which means better security and better social protection. In many developing countries, where incomes are low and jobs are predominantly based in agriculture, these benefits are lacking. One consequence of this is that child labour is still used to fill the income gap. The UNIDO report demonstrates the sharp drop in child labour as countries industrialize.

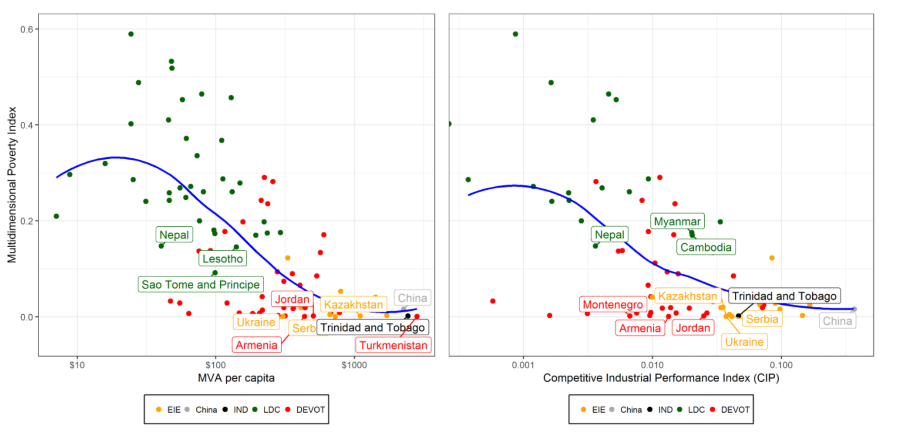

In addition, the improvements in incomes and jobs that drive economic growth are known to reduce poverty and boost living conditions. In countries that have industrialized, poverty, defined as living on less than $1.90 a day (2011, purchasing power parity), has decreased from around 10 per cent over the past two decades to almost zero.

Using the Multidimensional Poverty Index published as part of the UNDP Human Development Report series, which includes health, education, and standard of living for 100 developing countries since 2010, the drop in poverty in LDCs as they industrialized is particularly noticeable.

On education, which is fundamental for fostering the creativity and entrepreneurial spirit needed for sustainable economic development, the links are also clear. As countries industrialize, the demand for skilled labour goes up, encouraging more people to get the education needed for higher-paid jobs. At the same time, as the performance of the industrial sector improves, revenues increase, more tax is paid and more money can be invested in education.

This is once again reflected in the data, with a strong correlation between net enrolment for primary, and particularly secondary, education, and MVA per capita and the CIP Index. For example, in LDCs with low MVA per capita, secondary school enrollment is less than 50 per cent, compared to more than 80 per cent in industrialized countries (2017).

Before the COVID-19 pandemic struck, progress on the 17 SDGs to improve the lives of billions around the world had been steady but uneven. Now, with a decade to go before the goals expire, the economic and social impacts of the crisis threaten to reverse many of those gains.

The UN predicts that at least 71 million people could slide into poverty as a result of the economic impact of the current crisis. The disruption to education is exacerbating pre-existing inequalities for the poor, for girls, refugees and other vulnerable groups. Almost 24 million children and young people may lose access to education as a result of the pandemic, while progress on health indicators such as lowering maternal deaths rates, or controlling the spread of HIV/AIDS, could be derailed.

On current performance, SDG 9 will not meet its ambitions. One target – increase significantly industry’s share of employment and GDP and double it in LDCs – looks especially difficult to achieve, in large part because of stagnation in manufacturing in Africa’s poorest nations.

As the UN prepares to review SDG progress to date and sets out its vision for a decade of action, policymakers should remember what could be achieved by boosting inclusive and sustainable industrial development; and what is at stake in a world still grappling with the economic and social turmoil of COVID-19, in particular for LDCs, if industrialization is stalled.

Read the full report "How Industrial Development Matters to the Well-Being of the Population" here.

©EIF/Simon Hess.

If you would like to reuse any material published here, please let us know by sending an email to EIF Communications: eifcommunications@wto.org.