The EIF’s Daria Shatskova talks development in the world’s poorest countries with Daniel Gay, inter-regional adviser on least developed countries (LDCs) with the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA)

What is the LDC category and what does it mean for them to ‘graduate’?

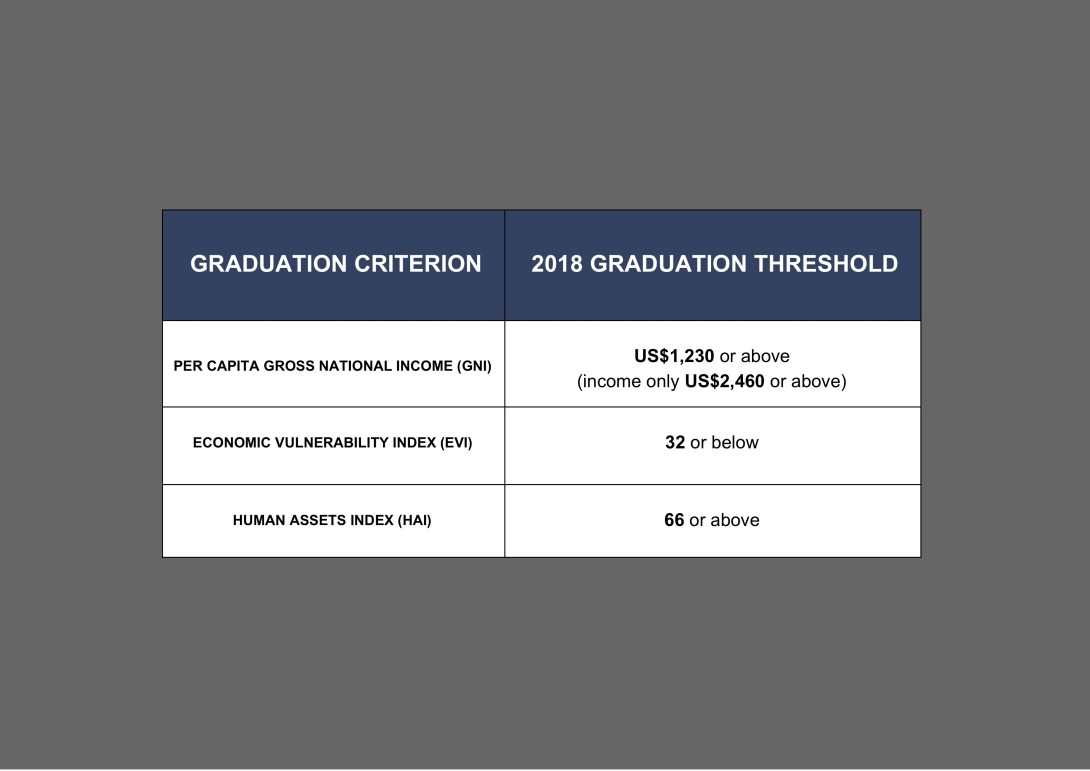

The least developed country category comprises the 47 most structurally vulnerable and economically disadvantaged countries. The category is made up of three criteria: economic vulnerability, human assets and per capita income. Each criterion is compiled using a number of subsidiary statistics.

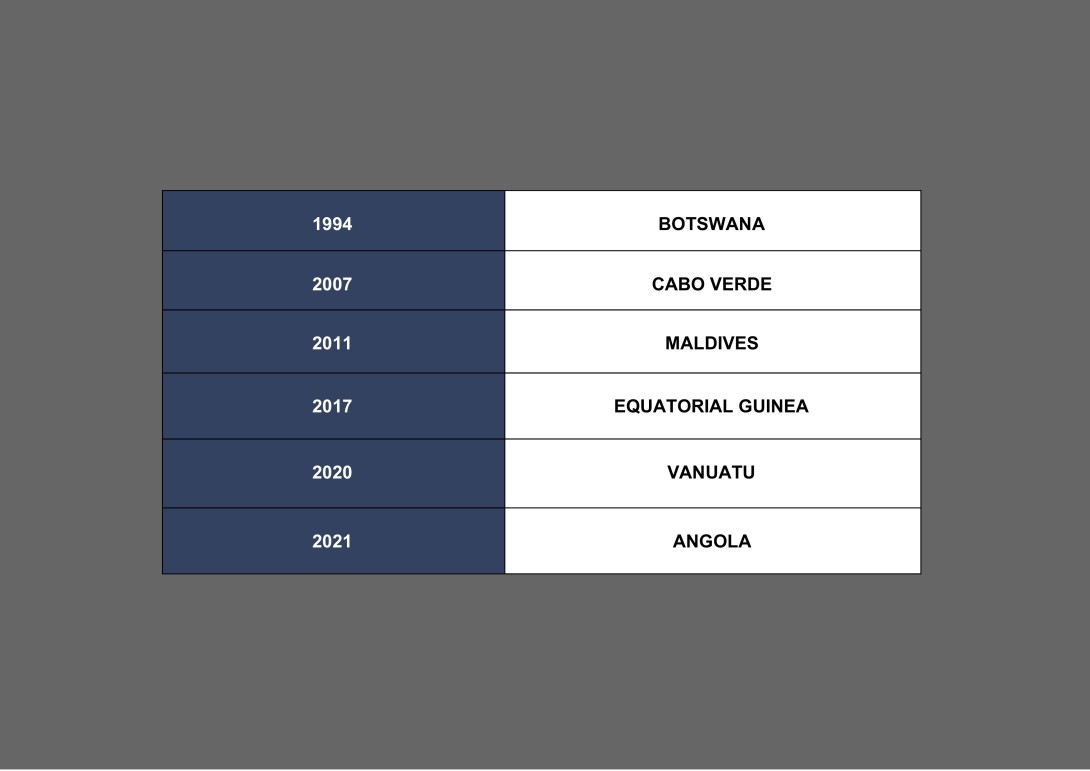

For a country to ‘graduate,’ at two consecutive triennial reviews of the UN Committee for Development Policy (CDP) it must meet two of these three criteria, or alternatively, per capita income must be at least twice the threshold – currently US$1,230 – using the World Bank Atlas method. Graduation from the category is a sign of progress. The idea is for countries to develop structurally – to move from low to high productivity economic activities. Graduation is a process of human development and greater income, and central to economic development.

Graduation can be viewed as a major milestone. For example, this year Bangladesh had a nationwide celebration hosted by the Prime Minister when Bangladesh met all three graduation criteria for the first time: real social and economic progress. We have built a website – www.gradjet.org – aimed at helping graduating LDCs understand where they stand vis-à-vis the graduation criteria, and at providing information, analysis and activities to support the process.

What are the most pressing challenges on the road to graduation?

The major challenge is building productive capacity for successful economic transformation. Many LDCs are not able to produce goods and services in sufficient quantity and quality for exports or to serve the domestic market. This to some extent slows the pace of economic growth and development. Some of these countries are stuck with undiversified low-production economies that are very much reliant on imports.

For many years countries have had duty-free, quota-free market access under the preference schemes set up by developed and developing countries, but this in itself, while helpful, has not been enough to spark structural transformation from low productivity to high productivity activities. There is an increasing focus on tackling directly the issue of productive capacity, on building up production of goods and services in a sustainable way.

Other challenges include environmental vulnerability, inequality, marginalization from global value chains, and of course the human side – education and health.

Can you highlight some specific successful examples of graduating LDCs and recent graduates?

Most of the successful LDCs managed to use economic policies to promote development of productive capacity and enjoyed political stability, as well as using foreign aid effectively. In several cases they were simply fortunate to be able to benefit from global economic trends.

For example, Vanuatu, which is going to graduate in 2020, leveraged a tourist boom, which was underpinned by state stability. International development assistance also helped: from Australia, the European Union, New Zealand, the United States, and other countries. This enabled the country to facilitate much needed investment and the growth of tourism. Recent LDC graduates such as Cabo Verde and Samoa also benefited from state stability, tourism and the use of international development assistance.

You mentioned Vanuatu, Cabo Verde and Samoa, which are among the Small Island Developing States (SIDS). What are key steps for them to cope with economic vulnerability?

Many small island countries are inherently economically vulnerable because a small number of industries or sectors dominate the economy. Some of these countries put in place policies to promote agriculture and sustainable manufacturing in small niche areas. Economic diversification helps to ensure long-term stability.

Environmental vulnerability is another concern. Small island developing states are also very vulnerable to climate change impacts like rising sea levels and extreme weather events such as cyclones in the Pacific. Climate change adaptation policies can help at least partially address this sort of vulnerability.

UNDESA has been taking stock of international support measures available to the LDCs. Can you share some international support measures that will remain available after LDC graduation? How can the global community support those countries?

The Committee for Development Policy Secretariat has created a website (www.un.org/ldcportal) cataloguing the various international support measures, which cover trade, official development assistance and other measures such as climate financing, reduced budgetary contributions to the UN and travel assistance.

Some donors and partners extend support measures for a certain period after graduation. For example, the European Union extends trade preferences for three years after graduation. So, countries still benefit from the preferences after they leave the category. Similarly, there are several other smooth transition measures aimed at phasing out this type of support.

The Enhanced Integrated Framework (EIF) has been extending support up to five years after graduation.

Other donors and partners might wish to follow the EIF in continuing to support these countries in building productive capacity on the ground with a view of achieving structural transformation in the long run.

One thing that is lacking is any positive incentive to graduate, other than the reputational benefits. Countries simply face a slower loss of support rather than any new special benefits for recent LDC graduates.

The countries that graduate risk the middle-income trap whereby they are no longer competitive on the basis of low costs and cheap labour, but they have not yet developed the technological sophistication or moved up the value-adding ladder far enough to leapfrog into upper middle-income status. So, they are stuck in this no man's land where they really need new sources of help, or revitalised economic policies, to promote development.

This is something that UNDESA is thinking about. One recent initiative is to help graduating LDCs along the Chinese ‘Belt and Road’ to conceptualize and enact new support measures aimed at tackling specific challenges on a country-by-country basis after graduation. The international community seems likely also to start taking those issues on board given the fact that more and more LDCs will graduate in the near future.

--------

For more details you can listen to the EIF Global Forum on Inclusive Trade for LDCs panel discussion with Daniel Gay on 'making the connections between inclusive trade, economic growth and LDC graduation' here.

--------

Daniel Gay is an inter-regional adviser on least developed countries (LDCs) with the Committee for Development Policy Secretariat of the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Daniel has focused particularly on the issues and challenges surrounding trade and LDC graduation. He is working on how to ensure that LDCs benefit as much as possible from international support measures directed at those countries, and which measures might help graduating countries after graduation.

Header image - ©Fernando Castro/EIF

If you would like to reuse any material published here, please let us know by sending an email to EIF Communications: eifcommunications@wto.org.