|

|

|

When sustainably exploited, fisheries can provide coastal communities, including populations in least developed countries (LDCs), with a source of protein and micronutrients essential for food security and adequate nutrition, as well as much-needed employment and income.

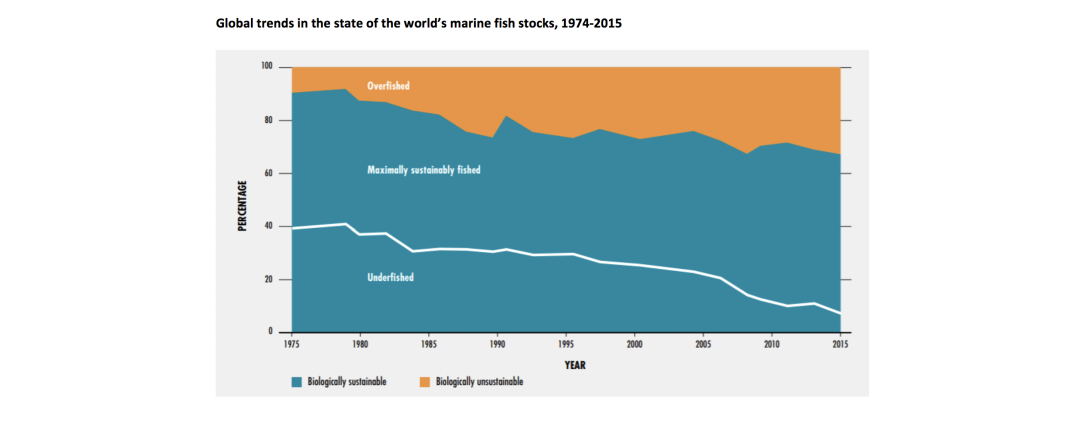

The ability of fisheries to continue to support food security and employment for growing populations is under pressure. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) latest State of the World Fisheries and Aquaculture report, 33 percent of assessed fish stocks are currently overexploited, with an additional 60 percent share of these stocks fished at their maximum sustainable level.

Global trends in the state of the world’s marine fish stocks, 1974-2015

Can the negotiation of fisheries subsidies rules at the World Trade Organization (WTO) help steer global fishing activity in a more sustainable direction, and how can LDCs be supported in this process?

Fisheries and subsidies matter

Fisheries are a crucial source of animal protein, livelihoods and export earnings for many developing countries, and for several LDCs. According to the FAO, in 2015, fish accounted for around 26 percent of animal protein intake in LDCs. A recent study by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) also highlights that in 14 of the (at the time) 48 LDCs, fisheries products were among the top five merchandise exports. One LDC, Myanmar, is among the top 20 producers of marine capture fish in the world.

Many LDCs both exploit their own fisheries resources and provide access to those resources for fleets of other countries, including distant-water developed and developing country fleets. These access arrangements are often an important source of revenue for resource-constrained LDC governments, but can create tensions between the rights of access provided to foreign industrial fleets and those afforded to domestic fleets.

Beyond their importance to food security and exports, fisheries are also deeply embedded in the social, economic and cultural fabric of many coastal LDCs. For many coastal communities, fishing is both part of their identity and the economic activity they have relied on when other opportunities are not available.

And subsidies matter. It is widely recognised today that fisheries subsidies are one of the major factors driving overfishing globally. When poorly designed, these support instruments can increase fishers’ incentives to fish at levels that are unsustainable.

What may look like effective measures to support the fishing sector in the short term often leads to the overcapitalisation of fleets and overfishing, which can jeopardise communities’ ability to sustainably exploit marine resources in the longer-term, leaving everyone worse off.

Several studies have shown that not all government support is equally harmful, however. Modelling by the OECD has demonstrated that support to income, for example, delivers benefits to fishers without much additional fishing effort. On the other hand, support in the form of subsidies to input costs, such as fuel, is very likely to lead to increased effort and risks of overfishing, without delivering much benefit to fishers’ incomes. Work by Rashid Sumaila has highlighted that some forms of support, to fisheries management efforts, encourage positive investment in fisheries resources.

Negotiating international rules on fisheries subsidies

World Trade Organization members are currently negotiating new rules to discipline the provision of subsidies to fishing industries. Unusually for the WTO, the negotiation is motivated primarily by the effects of these subsidies, through economic activity, on the marine environment – the original mandate calls for a prohibition on “certain subsidies that contribute to overcapacity and overfishing.”

The negotiations are also targeting a link between subsidies and ocean governance: Sustainable Development Goal target 14.6 assimilated the WTO mandate and also called on members to eliminate subsidies to illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing. Both the original mandate and SDG target 14.6 underline the importance of “appropriate and effective” special and differential treatment for developing and least developed countries in light of the importance fisheries have in their sustainable development.

There are three main substantive rules on the table in the negotiations: a prohibition of subsidies to IUU fishing, a prohibition of subsidies to fish stocks that are already overfished and a broader prohibition (per the original mandate) on subsidies that contribute to overcapacity and overfishing. Negotiators are also beginning to think about how the disciplines will be implemented, and what support might be available to do so.

Special and differential treatment is being treated as a cross-cutting issue; a question to be addressed with respect to the overall burden of the new rules. At this stage, options for special and differential treatment include longer timeframes for implementation, technical assistance and in some cases exemptions from some of the new rules, in particular new disciplines on capacity and effort-enhancing subsidies. LDCs have themselves proposed that the prohibitions on subsidies to IUU fishing and to the fishing of overfished stocks apply to them, recognising the gravity of the challenges such disciplines aim to address.

Policy impacts of new subsidy rules on least developed countries

Implementing new WTO rules on fisheries subsidies will have a range of policy impacts for LDCs. They will need to assess how they wish to implement the prohibition on subsidies to IUU fishing; perhaps by adding a subsidy prohibition to existing domestic sanctions for illegal fishing.

Improving the monitoring, control and surveillance of fishing activity – both by domestic and foreign fleets – within their exclusive economic zone could help LDCs to implement an IUU subsidy rule more comprehensively. LDCs may also find it useful to establish the state of their most economically valuable fish stocks – using either data-intensive or data-poor methods. Then, where those stocks are overfished, determine how subsidies for the fleets that fish them could be reformed.

Reforming subsidies can also contribute to climate change adaptation. There is already evidence that warming ocean temperatures are leading to fish stocks moving to higher latitudes and deeper waters. Healthy fish stocks are more resilient to the pressures of climate change than overfished stocks. To the extent that reforming subsidies contributes to healthier fish stocks, reform would help fish stocks and the broader ocean ecosystem to adapt gradually to changes driven by climate change, and therefore also provide communities that depend on fisheries for livelihoods with a longer timeframe to adapt to these changes.

Role of aid for trade

Aid for trade can contribute, in at least three ways, to supporting LDCs to redesign subsidy programmes and implement a new WTO agreement on fisheries subsidies.

First, aid for trade could help LDC governments to fully understand the exact implications of new WTO rules by looking at existing programmes and policies and mapping what needs to be changed, reformed or improved as a result of new disciplines – perhaps in the context of an examination of the fisheries sector and its role in economic diversification and trade-supported sustainable development.

Second, aid for trade could help governments and stakeholders to establish how to give effect to new disciplines, including identifying how to link subsidies policies with fisheries management decisions – for example phasing out subsidies for stocks that are overfished. Aid for trade, in this context, could complement other technical assistance that might be available to help strengthen fisheries management, for instance for stock assessment and better monitoring fishing in their waters.

Third, aid for trade could be used to support subsidy reform pathways that help LDCs to comply with their new obligations under an eventual WTO agreement, while actively managing the impacts of reform on their most vulnerable communities. In particular, aid for trade could be used to help fishing communities in LDCs to address supply-side and infrastructure constraints, like storage and processing capacities, to help them add value to their catch before it is onsold, which could potentially help to support incomes through a period of subsidy transition.

Organisations like the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), with an extensive track record of supporting countries to design subsidy reform pathways, will also be well-placed to help in this effort.

----------

* Alice Tipping is Lead, Fisheries Subsidies at the International Institute for Sustainable Development. Tristan Irschlinger is a Policy Advisor, Fisheries Subsidies at the International Institute for Sustainable Development.

--------

This policy series has been funded by the Australian Government through the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The views expressed in this publication are the author’s alone and are not necessarily the views of the Australian Government.

If you would like to reuse any material published here, please let us know by sending an email to EIF Communications: eifcommunications@wto.org.