The collapse in trade provoked by the coronavirus pandemic has exposed the fragility of carefully constructed supply chains in the global fashion industry, and the asymmetries with which they are governed.

The day shift is set to begin. As dawn rises over the city of Antsirabe in the central highlands of Madagascar, morning prayers and traditional Malagasy chants sung by hundreds of machine operators resound through the Socota garment factory. After a minute of silence and shuffling, the buzzing of over 2,000 cutters, sewers and pressers gradually build to a crescendo that will rhythm the plant until dusk. In the adjacent textile factory, cotton-weaving machinery stutters loudly and rolls out yards of dyed and printed fabric destined to be assembled by these garment workers into shirts, trousers and other clothing for shipment to retail stores around the globe.

The livelihoods of these employees – numbering around 7,000 on Socota’s industrial site – is at risk. With the global fashion industry estimated to contract by 27-30% in 2020, many clothing manufacturers in developing countries are closing down due to the demand shock induced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Madagascar is among the world’s poorest countries, with over three-quarters of its 26 million population living in poverty. In the absence of household savings and social safety nets, this loss of employment will plunge many of the factory’s low-skilled workers and their dependants into deprivation.

Sustainable export strategies?

The threat to the survival of Socota’s textiles and clothing operations raises difficult questions regarding the sustainability of export-led development strategies in poor countries based on integration into global value chains.

Apparel is a conventional starter industry for low-income countries engaged in export-oriented industrialisation. The enactment of export processing zone legislation in 1989, and preferential market access to Europe, the United States and South Africa, helped Madagascar attract inward investment and diversify into labour-intensive manufacturing. Garment production has since served as the economy’s main driver of growth in exports and formal employment creation, contributing to a third of total goods exports and well over 100,000 jobs.

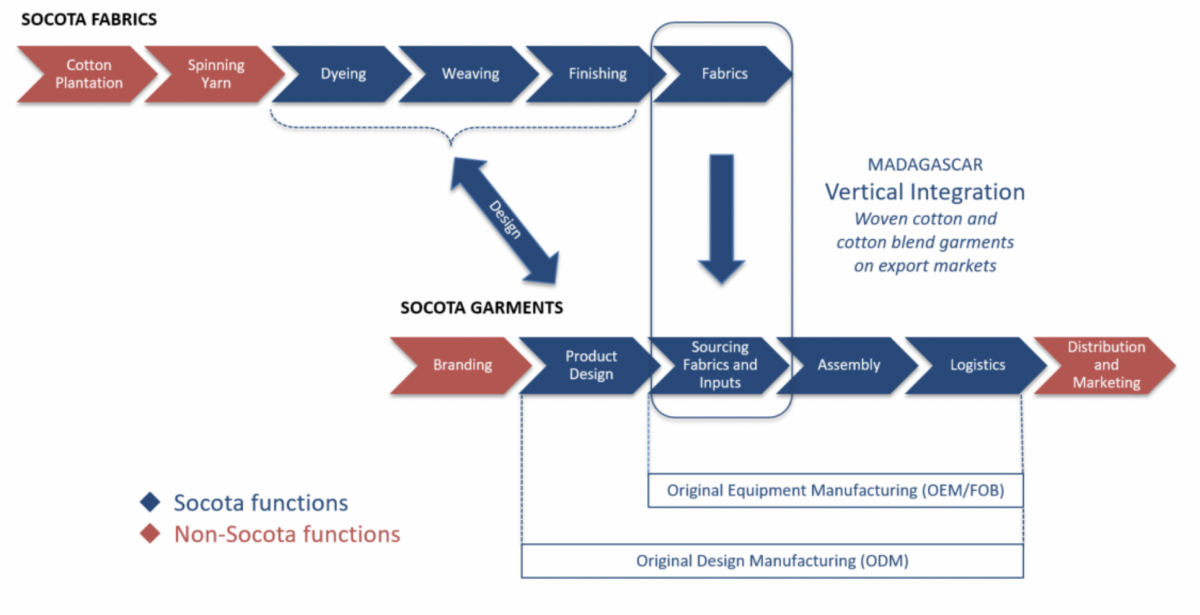

Socota’s journey is somewhat atypical for sub-Saharan Africa. The company was established close to 100 years ago and is deeply embedded in Madagascar’s developmental history. Its textile mill is recognised as one of the flagships of domestic industry, specialising in the production of woven cotton fabrics – a capital-intensive segment of the supply chain with high barriers to entry usually located in more developed nations. The company has also become one of the largest garment manufacturers on the Indian Ocean island. This dual specialisation has enabled the firm to pursue an export-led strategy based on vertical integration (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Capturing value-adding activities in value chains is challenging for low-income producers

Source: author, adapted from IMD (2014).

Firm-level insights

Socota’s industrial expansion in Madagascar offers insights into how textiles and clothing production in a poor and remote country can build resilience to shocks and result in economic and social upgrading.

Internationally, the firm has adapted to fundamental changes in trade rules subsequent to the phase-out of the MultiFibre Arrangement in 2005 which led to a profound reorganisation of world production and retail. Socota has also responded to Asian competition and the fallout from the 2008 global financial crisis. Domestically, the company has withstood recurrent political crises that have rocked Madagascar since independence in 1960 and hindered the island’s development.

To succeed, Socota has endeavoured to meet the traditional sourcing criteria of lead firms in the buyer-driven value chain – costs, quality and reliability. Through its vertical set-up, the firm has also developed its capacity to respond to newer criteria required of fast-fashion suppliers – short lead times, production flexibility, sourcing, product development, inventory management and logistics.

In addition, a commitment to business sustainability has improved the conditions of workers and brought progress in the community. Corporate schemes range from health benefits, training and gender diversity in management to wastewater recycling and transitioning to low-carbon energy.

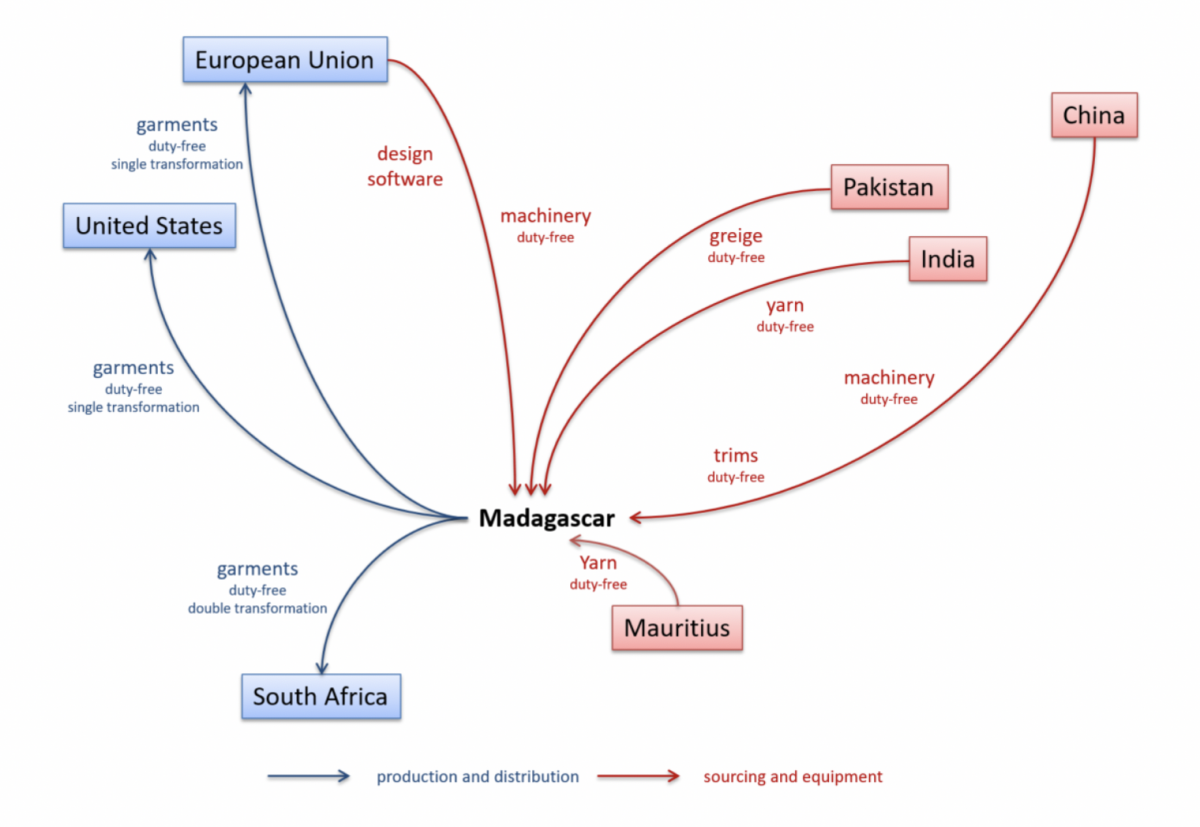

As a result, the company has positioned itself as a supplier of choice in fiercely competitive garment sourcing networks, and developed a diversified customer base consisting primarily of European, South African and US brand owners and retailers like Camaïeu, Woolworths and Zara (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Complex sourcing and distribution networks pivot around production in Madagascar

Note: the graph illustrates a simplified snapshot of Socota’s sourcing and distribution activities. “Single” and “double” transformation refers to rules of origin in destination markets.

Source: author, adapted from IMD (2014).

Pandemic impacts

It is against this backdrop that retailers have cancelled orders and frozen contracts in response to plummeting consumer demand due to coronavirus lockdowns. Purchases of items in production and even ready to ship have been annulled, while contracts under negotiation for 2021 collections have been broken off.

In many instances, lead firms in the global fashion industry have essentially passed the sudden demand shock on to their suppliers in developing countries who have little power to object and are least equipped to buffer the impacts.

In Madagascar, private enterprises and their employees have not benefitted from government-funded emergency rescue schemes or temporary income support as has been the case for retailers and workers in wealthier economies.

Workers at the Socota garment factory in Antsirabe, Madagascar

Socota has reorganised weekly rotating shifts and put in place measures like paid leave and loans to maintain social cohesion and ensure workers have sufficient earnings and immediate funds to feed themselves and their families. However, with a precipitous decline in revenue, a point will be reached where this cash flow is no longer available. To keep the factory running, the firm has turned to manufacturing personal protective equipment for the European market, which provides temporary reprieve.

Rethinking value chains

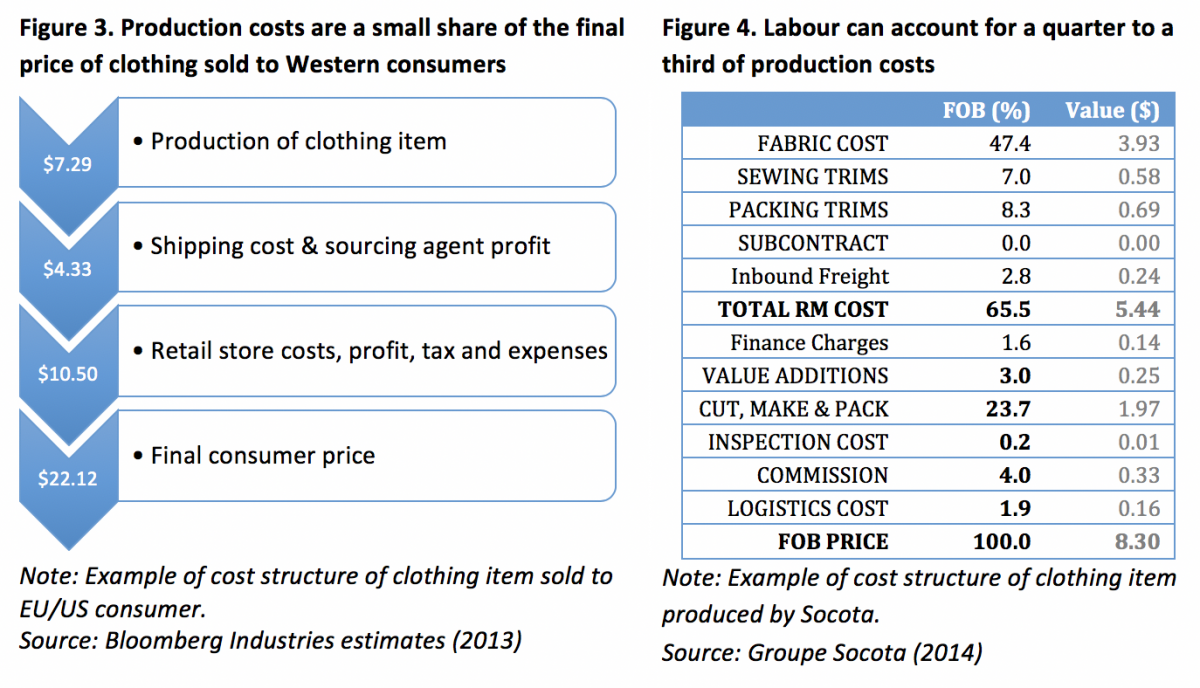

An upshot of this crisis is that it could finally lead to a rethink of how value is distributed in the global fashion industry – characterised by strong power asymmetries between producers and buyers. Lead firms perform high value-adding activities like R&D, design, branding and retailing, while manufacturing is outsourced to a dispersed web of supplier firms mostly found in low-wage countries and often operating on razor-thin margins. The complexity, speed and range of operations demanded of suppliers at ever lower costs has increased.

Retail has experienced an extraordinary degree of consolidation over the past two decades. Analysts estimate that in 2019, 97% of profits in the US$2.5 trillion fashion industry were generated by just 20 companies. Greater consolidation is expected as retailers and manufacturers fail to survive the crisis. This degree of concentration in the distribution of rewards should cause pause for reflection in a global industry which employs some of the world’s poorest and most vulnerable workers, including a high share of women.

Sustainable production that responds to legitimate consumer preferences for ethical fashion challenges the distribution of profits across the value chain (Figures 3 & 4). Yet sound labour and environmental practices are rarely governed by positive incentives like price premiums, support programmes and longer contracts – all of which would enable investment in plant and equipment upgrades and promote better paid, more secure and cleaner jobs in poor countries.

Governments of producer countries, for their part, must uphold their responsibility to create an environment that is conducive to enterprise, enables domestic businesses to be competitive and enforces compliance with domestic regulations. Sadly, these are policy areas where lawmakers in Antananarivo have often been found wanting.

Labour-intensive manufacturing can play a key role in reducing poverty in Madagascar. As things stand, any extended period of unemployment for the tens of thousands of low-skilled workers who toil in the island’s clothing factories will imply hunger and suffering. Moreover, should a company like Socota fail to weather the storm, decades of investment in industrial development embedded in the community would be lost.

In a spirit of positive disruption, actors in the global fashion industry could seek to re-engineer the organisation of value chains, guided by approaches that give greater consideration to principles of equity and sustainability for the better of producers and workers in poor countries.

_____

Parts of this article are derived from the business case study on Groupe Socota authored by Fabrice Lehmann and published in the book New Realities by IMD Business School.

Header image of a man in Bangladesh - ©Bryon Lippincott via Flickr Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) license.

If you would like to reuse any material published here, please let us know by sending an email to EIF Communications: eifcommunications@wto.org.