|

|

|

Participation in value chains has been a key plank of low-income country development strategies over the past generation. Many analysts and businesses are anticipating a period of transformation that will see a wide-ranging overhaul of supply chain configuration.

The organisation of international production and investment is entering a new phase driven by powerful undercurrents – which have been laid bare or given added momentum by the impacts of COVID-19 on economies and societies worldwide.

[related-article]

Forces at play include the adoption of fourth industrial revolution technologies, the rise of political and economic nationalism, the urgent need to address environmental sustainability and the greater frequency of shocks to the global trading system emanating from endogenous and exogenous risks like extreme weather events, pandemics, cybersecurity and financial crises.

As the supply chain management decisions of multinationals and lead retailers adjust to this new environment, what are the implications for less developed countries?

Poor country participation in value chains

Since the early 1990s, many least developed countries (LDCs) have tried to emulate the export-led industrialisation model followed to good effect by several Asian economies. To achieve this, they have sought to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) – mostly efficiency- and resource-seeking – and to link their domestic sector to foreign markets through participation in global value chains (GVCs). A sizeable share of LDC exports are now routed through such chains, which represent up to 40% of international trade.

While the strategy has seen pockets of success, outcomes have generally been disappointing from a developmental perspective. Increased participation has mostly failed to boost productive capacity growth or stimulate a process of structural transformation. The economy-wide spillover effects of integration have been relatively small, with the technological and organisational benefits correlated with exports often limited to a narrow set of firms and activities. Decent jobs have not been created at sufficient scale and countries have struggled to capture value and upgrade.

In addition, trade and FDI growth have declined since the 2008 financial crisis, which has left LDCs competing for a shrinking pool of capital and reduced opportunities to integrate.

At present, LDC firms tend to perform low value-added and labour-intensive tasks in supply chains in primary industries (extractive and agro-based), low-tech industries (textiles and apparel), processing industries (food and beverage) and entry-level services. Here we mainly consider the agri-food and apparel value chains, which are buyer-driven, fragmented and geographically distributed.

Resilience and agility in supply chain management

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the fragility of supply chains, and rebuilding with resilience has become a mantra of business and policy circles. These vulnerabilities may have crystallised awareness among lead firms that “the distributed global business model, optimised for minimum cost, is finished.”

The outsourcing and offshoring model that has propelled globalisation for the past 30 years has been guided by costs, especially labour. Due to rising wages in developing countries and technological advances that substitute for manual tasks, labour arbitrage is no longer the primary factor driving investment and sourcing decisions. Hidden costs related to risks tied into the pursuit of supply chain resilience have surfaced during the pandemic. Supply chain stress tests will become the norm.

The need for agility in the supply chain is not new. But the COVID-induced disruptions – and the uncertainty that lies beyond – has served to make the realisation starker. The sourcing criteria of multinationals have expanded to respond to changes in consumer preferences. Beyond costs and quality, they comprise flexibility and short lead times. The EY Future Consumer Index has identified new consumer segments that will emerge from the pandemic. Firms that adapt to these behavioural shifts will have digitalised and invested in differentiation. Adjustments in supply chain logistics and sourcing networks will accompany this change.

Multiple sourcing and proximity sourcing

Two long-term trends are taking shape as lead firms hardwire resilience and agility into their supply chains: multiple sourcing and proximity sourcing.

Multiple sourcing refers to diversification of the supply base, and will impact industries relevant to LDCs like agri-food and low-tech manufacturing. The goal is to reduce vulnerabilities associated with single-source dependencies and excess concentration in a region or supplier. The key drivers include state incentives for stable supplier networks, cost differentials and digitalisation. This diversification will increase the distribution and fragmentation of supply chains in affected sectors. Governance will become more platform based – typified by low FDI intensity and high propensity to regulate through private standards. Digital technologies are giving rise to new tools for supply chain risk management and monitoring capacities that enhance traceability across multi-tiered sourcing networks.

Proximity sourcing denotes reshoring and nearshoring. Supply chains become shorter and regional – with a possible rebundling of certain intra-firm activities. Proximity sourcing is influenced by new technologies like automation, the shift towards sustainability and a policy environment pushing for self-reliance and the build-up of strategic industrial capacities. Accelerated speed to market and lower supply chain coordination costs are also important determinants. Intra-regional trade and market-seeking FDI will increase as lead firms relocate and diversify supply chain segments. Reshoring will reduce GVC trade and efficiency-seeking investment.

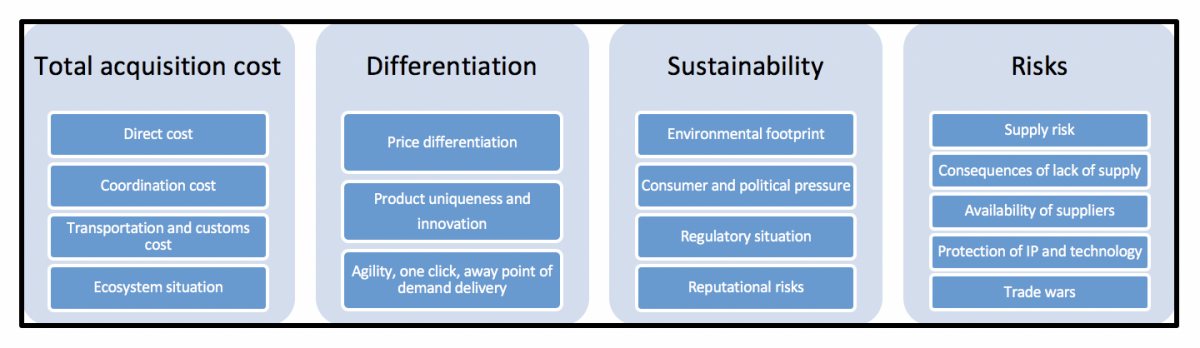

Main relevant factors firms will consider in nearshoring decisions

Source: Carlos Cordon and Jørn B. Andersen, Recasting the Global Bargain – A Future Model for Supply Chain Location (forthcoming).

Opportunities in transformed value chains

The new supply chain trajectories offer pointers for policymakers in developing countries seeking to maximise the benefits from integration.

The support measures implemented by many governments in response to COVID-19 have led to a policy environment shaped by greater state interventionism. This creates the space for industrial policy strategies in LDCs designed to help disseminate the gains from GVC participation to the rest of the economy. Such strategies lay emphasis on domestic productive integration and proactive engagement and learning between governments, global firms, local suppliers and the workforce.

In particular, the adoption of new technologies by lead firms is placing new demands on participants in the supply chain, as competitive advantage relies more on skills, services and infrastructure. Skill-biased technological change could erode LDC comparative advantages and exacerbate the value added gap between countries.

But there will be opportunities for poor countries in the transformations that lie ahead. They can capture investment as lead firms look to diversify their supply base in agriculture and less automated industries. Proximity sourcing will give rise to regional value chains and investments that could enable a build-up in industrial capabilities. Digitalisation improves market access for small businesses and makes possible the growth of services for export. Productivity gains generated by new technologies in developed countries could also increase demand for intermediate inputs sourced from LDCs.

Value chains create strong interdependencies across countries – as tangibly felt during the recent shock. International economic cooperation is of critical importance in enabling LDCs to reach their potential in this period of change. Priority areas to consider include regional cooperation in trade and investment and collaboration at the global level on issues like taxation and data.

Navigating turbulence

Governments and businesses have had no dress rehearsal for the extraordinary events set in motion by COVID-19. Huge uncertainty hangs over the economic recovery and what a post-pandemic world will look like.

Future policy developments are highly unpredictable. And there is no standard framework to help anticipate the strategies global firms will put in place for the organisation of their supply chains. Poor countries face considerable risks in this new environment.

-----------------

This article is jointly published by IMD here, and Trade for Development News.

Header image of a woman processing cashews in The Gambia - ©Ollivier Girard/EIF

If you would like to reuse any material published here, please let us know by sending an email to EIF Communications: eifcommunications@wto.org.